© Liz May 2018

Articles

© Liz May 2024

NEWS photo Cindy Goodman

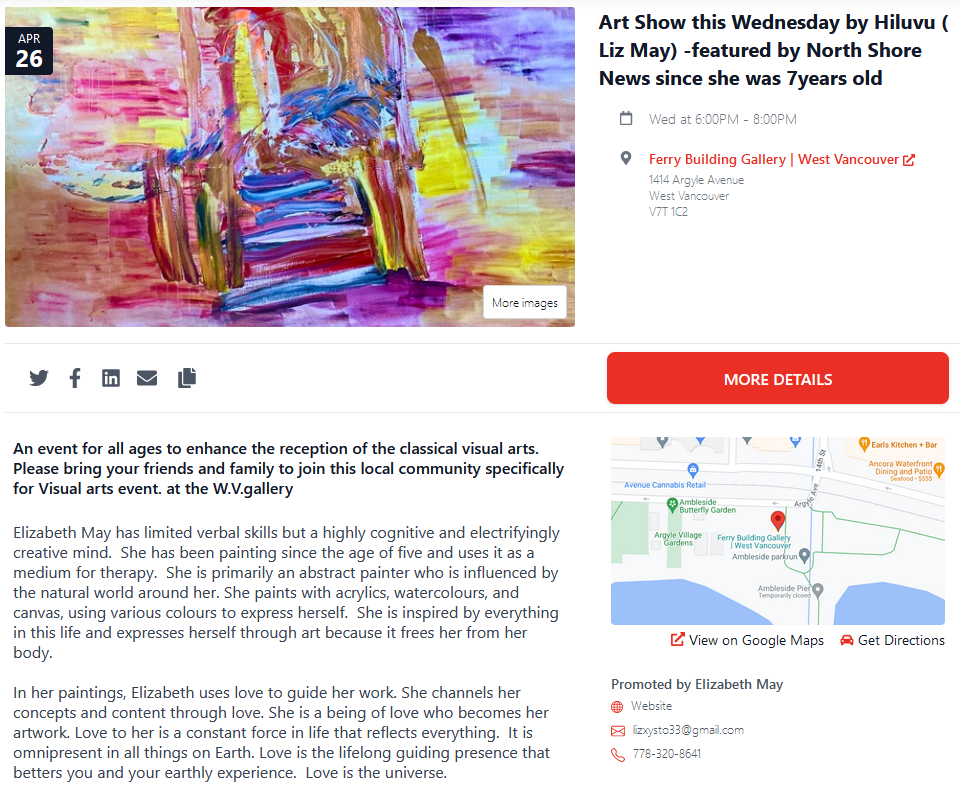

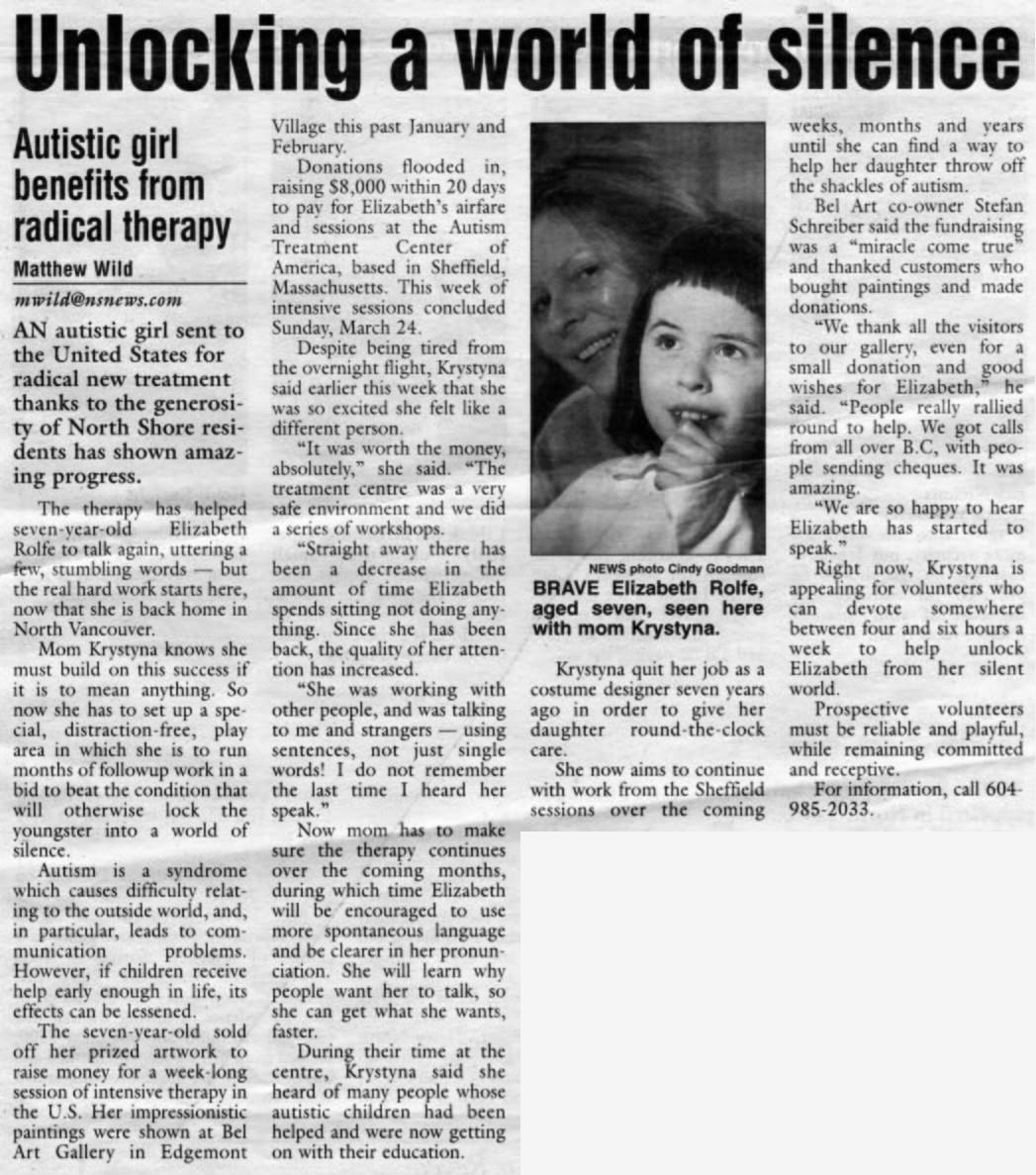

A youngster with autism is selling her artwork in a bid to raise money for a new type of treatment. Seven-year-old Elizabeth Rolfe has handed her prized paintings over to mother Krystyna (also pictured) to go on show at Bel Art Gallery, Edgemont Village, starting Friday.

Art sale to fund autism treatment

Matthew Wild newsroom@nsnews.com

HEALTH cutbacks are going to hit children like Elizabeth.

The seven-year-old has autism, and needs much care and support just to do the things other children her age take for granted. Unable to communicate, she remains locked in her own world.

The youngster is going to auction her prized artwork later this month in a bid to raise cash for extra treatment. Her mother, Krystyna Rolfe, a North Vancouver resident, wants to take Elizabeth for intensive therapy in Massachusetts.

Autism is a syndrome which causes difficulties communicating and relating to the outside world, but if treatment is given early enough in life its effects can be lessened. Rolfe is pinning her hopes on the one-week intensive Son Rise Program run by the Autism Treatment Center of America, in Sheffield, Ma.

Rolfe has used up her savings, and borrowed money from friends to collect $3,000 towards the sessions, but she has to raise a further $3,000 by February. A single mother who formerly worked as a costume designer for movie-makers, she has been unable to work for the past seven years as Elizabeth requires around-the-clock care.

Approximately 20 of Elizabeth's paintings will go on display at Bel Art Gallery, 3053 Highland Blvd., North Vancouver, between Friday, Jan. 11 and Feb. 2, in an exhibit titled Art from Autism. There will be an opening children's day between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. on Saturday, Jan. 12. The work is likely to be auctioned off at the end of the display.

Said Rolfe, "Elizabeth was diagnosed autistic when she was four, but we have not had any follow-up work since then, with no treatment offered. The government gives no money for autistic children.

"She had language but she lost it. I communicate with her by showing her photographs. Elizabeth was talking before she was two but stopped at the age of four.

"She cannot go to school any more because they don't know what to do with her. They have tried to treat her as a regular child, but she gets frustrated that she cannot communicate. She went to school in September for a couple of weeks, but has been home since. I hope she will start a new school in January."

Bel Art co-owner Beatrice Schreiber said the gallery supports community work and she was particularly touched by Elizabeth's story.

"I like her artwork very much," said Schreiber. "It's abstract, and very interesting because her spirit shines through in these paintings. She has no other way of communicating.

"She is a little girl who has totally opened our hearts. She is only young, and needs treatment right away. We are giving the gallery space for free so that whatever money is made is given for this treatment."

This lack of educational and healthcare support is typical of the plight faced by autistic people throughout the area, according to the Autism Society of British Columbia which warns of further massive cuts to the already scant services people with autism can access.

Said its executive director, Deborah Pugh, "Christina and Elizabeth are a perfect example of the kind of family that will fall between the gaps in healthcare when cuts are made.

"Elizabeth was diagnosed early on, being quite severely affected. Some children with milder forms of autism may be going undiagnosed. They may have language but do not know how to use it, and have little social awareness. They are often bullied at school, where they can do very badly despite being bright."

She said early diagnosis and support is vital so children with autism can learn to communicate and share in family life. Although incurable, some children, if caught early enough, can largely overcome their symptoms. However, if children are not taught communication skills, frustration can cause behaviour problems.

Pugh, a North Shore mother of an autistic child, said families throughout the area will be hit by a 40 per cent cut from the provincial budget projected to provide intensive treatment for all children under six with autism by the end of 2003.

On Aug. 9, 2001, Minister of Children and Family Development Gordon Hogg told the legislature that $19.85 million had been budgeted for autism treatment. Yet in November he announced the budget had been cut to less than $11 million. This, said Pugh, makes it impossible for the government to keep its pre-election promise to provide early intensive treatment for youngsters.

Pugh says cuts mean children will be "abandoned to their disability" with between 200 and 300 B.C. pre-schoolers denied early treatment.

Meanwhile, the government is to appeal a landmark court decision of July 2000, in which the B.C. Supreme Court ordered it to fund treatment for pre-schoolers with autism. It is also examining further health-related budget cuts, with ongoing talks about cutting 10 per cent in each of the next three years from the Ministry of Children and Family Development budget.

"Services for the most needy people in the province are going to be slashed," said Pugh. "There will be devastating consequences for families which depend on respite care, speech therapy and occupational therapy."

This, she said, will "dash the hopes" of many families of ever receiving respite care or "behaviourable" support.

"They will be cutting services for young children with autism," said Pugh. "That's when treatment is most vital."

Pugh claimed cuts are unlikely to save money overall as children with autism will now be more likely to be placed into foster or group homes. She fears teenagers and adults with autism will end up on the Downtown Eastside, and that family break-ups will increase along with reliance on welfare, and that pressure on the education system will intensify.

According to latest research, autism occurs in as many as one person in 160. It is not a mental illness, but the result of a neurological disorder affecting the functioning of the brain in the areas of social interaction and communication skills. Symptoms include difficulties in verbal and non-verbal communication, social interactions, and leisure or play activities.

Some adults with autism can live and work independently in the community, while others need daily support. Health experts agree that early intervention results in dramatically positive outcomes for young children with autism.

According to Sunny Hill Centre for Children, in Vancouver, an intervention program should feature at least 15 hours a week of highly structured, predictable and routine work to build up communication skills and social behaviour.

The centre also says it finds children with autism need training in functional living skills at the earliest possible age, including help in learning to cross a street safely, make a simple purchase or ask for help.

Art sale to fund autism treatment

Matthew Wild newsroom@nsnews.com

HEALTH cutbacks are going to hit children like Elizabeth.

The seven-year-old has autism, and needs much care and support just to do the things other children her age take for granted. Unable to communicate, she remains locked in her own world.

The youngster is going to auction her prized artwork later this month in a bid to raise cash for extra treatment. Her mother, Krystyna Rolfe, a North Vancouver resident, wants to take Elizabeth for intensive therapy in Massachusetts.

Autism is a syndrome which causes difficulties communicating and relating to the outside world, but if treatment is given early enough in life its effects can be lessened. Rolfe is pinning her hopes on the one-week intensive Son Rise Program run by the Autism Treatment Center of America, in Sheffield, Ma.

Rolfe has used up her savings, and borrowed money from friends to collect $3,000 towards the sessions, but she has to raise a further $3,000 by February. A single mother who formerly worked as a costume designer for movie-makers, she has been unable to work for the past seven years as Elizabeth requires around-the-clock care.

Approximately 20 of Elizabeth's paintings will go on display at Bel Art Gallery, 3053 Highland Blvd., North Vancouver, between Friday, Jan. 11 and Feb. 2, in an exhibit titled Art from Autism. There will be an opening children's day between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. on Saturday, Jan. 12. The work is likely to be auctioned off at the end of the display.

Said Rolfe, "Elizabeth was diagnosed autistic when she was four, but we have not had any follow-up work since then, with no treatment offered. The government gives no money for autistic children.

"She had language but she lost it. I communicate with her by showing her photographs. Elizabeth was talking before she was two but stopped at the age of four.

"She cannot go to school any more because they don't know what to do with her. They have tried to treat her as a regular child, but she gets frustrated that she cannot communicate. She went to school in September for a couple of weeks, but has been home since. I hope she will start a new school in January."

Bel Art co-owner Beatrice Schreiber said the gallery supports community work and she was particularly touched by Elizabeth's story.

"I like her artwork very much," said Schreiber. "It's abstract, and very interesting because her spirit shines through in these paintings. She has no other way of communicating.

"She is a little girl who has totally opened our hearts. She is only young, and needs treatment right away. We are giving the gallery space for free so that whatever money is made is given for this treatment."

This lack of educational and healthcare support is typical of the plight faced by autistic people throughout the area, according to the Autism Society of British Columbia which warns of further massive cuts to the already scant services people with autism can access.

Said its executive director, Deborah Pugh, "Christina and Elizabeth are a perfect example of the kind of family that will fall between the gaps in healthcare when cuts are made.

"Elizabeth was diagnosed early on, being quite severely affected. Some children with milder forms of autism may be going undiagnosed. They may have language but do not know how to use it, and have little social awareness. They are often bullied at school, where they can do very badly despite being bright."

She said early diagnosis and support is vital so children with autism can learn to communicate and share in family life. Although incurable, some children, if caught early enough, can largely overcome their symptoms. However, if children are not taught communication skills, frustration can cause behaviour problems.

Pugh, a North Shore mother of an autistic child, said families throughout the area will be hit by a 40 per cent cut from the provincial budget projected to provide intensive treatment for all children under six with autism by the end of 2003.

On Aug. 9, 2001, Minister of Children and Family Development Gordon Hogg told the legislature that $19.85 million had been budgeted for autism treatment. Yet in November he announced the budget had been cut to less than $11 million. This, said Pugh, makes it impossible for the government to keep its pre-election promise to provide early intensive treatment for youngsters.

Pugh says cuts mean children will be "abandoned to their disability" with between 200 and 300 B.C. pre-schoolers denied early treatment.

Meanwhile, the government is to appeal a landmark court decision of July 2000, in which the B.C. Supreme Court ordered it to fund treatment for pre-schoolers with autism. It is also examining further health-related budget cuts, with ongoing talks about cutting 10 per cent in each of the next three years from the Ministry of Children and Family Development budget.

"Services for the most needy people in the province are going to be slashed," said Pugh. "There will be devastating consequences for families which depend on respite care, speech therapy and occupational therapy."

This, she said, will "dash the hopes" of many families of ever receiving respite care or "behaviourable" support.

"They will be cutting services for young children with autism," said Pugh. "That's when treatment is most vital."

Pugh claimed cuts are unlikely to save money overall as children with autism will now be more likely to be placed into foster or group homes. She fears teenagers and adults with autism will end up on the Downtown Eastside, and that family break-ups will increase along with reliance on welfare, and that pressure on the education system will intensify.

According to latest research, autism occurs in as many as one person in 160. It is not a mental illness, but the result of a neurological disorder affecting the functioning of the brain in the areas of social interaction and communication skills. Symptoms include difficulties in verbal and non-verbal communication, social interactions, and leisure or play activities.

Some adults with autism can live and work independently in the community, while others need daily support. Health experts agree that early intervention results in dramatically positive outcomes for young children with autism.

According to Sunny Hill Centre for Children, in Vancouver, an intervention program should feature at least 15 hours a week of highly structured, predictable and routine work to build up communication skills and social behaviour.

The centre also says it finds children with autism need training in functional living skills at the earliest possible age, including help in learning to cross a street safely, make a simple purchase or ask for help.